In last week’s blog post, we covered the King Farouk collection of World Paper Money and the subsequent sale of the Latin American section in a 1972 auction. First of all, a correction for that blog pointed out by an observant reader. The Farouk sale was cataloged by Fred Baldwin, not by John Synge, who merely organized the items.

This week, we will take the discussion further, and look at the obstacles and limitations of pedigree research for world paper money. Unlike coins, and to a certain extent U.S. paper money pedigree research, researching pedigrees for world paper money is still in its infancy, and is further complicated by lack of available resources. However, as this blog post will show, your author believes that there is value in obtaining pedigree information for world paper money.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the word pedigree in our context as follows:

The origin and the history of something.

In numismatics, very rarely can a pedigree be traced back to the year of production. Ancient coins often have lengthy pedigrees, and in that field pedigree research is extremely important as regulations put fewer limitations on trading if it can be proven that the item has been in collections for a long time and is not a recent find. There are some U.S. coins that have a complete or virtually complete, unbroken pedigree back to the mint. For example, in our Spring 2022 auction, we offered an 1898 quarter in NGC Proof-69 with the following pedigree:

Provenance: From the Dr. Paul and Rosalie Zito Collection. Acquired on May 13, 1997. Earlier ex J.M. Clapp, who acquired it directly from the Philadelphia Mint, November 1898; John H. Clapp; Clapp estate, 1942, to Louis E. Eliasberg, Sr.; our (Bowers and Merena’s) sale of the Eliasberg Collection, April 1997, lot 1564.

For paper money, and especially world paper money, it’s more complicated. First of all, paper money has not been around as long as coins. Secondly, catalog listings prior to the 1970s are often brief and lack detail (as we saw in last week’s blog post). Finally, due to restrictions around reproducing images of currency few (if any) early catalogs have pictures of notes. Stamp collectors are familiar with a practice in that industry of picturing just half a stamp, but that technique does not seem to have carried over to numismatic auction catalogs.

Yet, I believe it is important for pedigrees to be studied and recorded. There are two primary reasons for this:

1. A pedigree allows a note to be traced, along with its history, from collection to collection. If you have a note imaged with a cancellation in an old catalog that is now uncancelled, something is up.

2. More importantly, it is neat to say you own a piece of paper money with a pedigree going back x number of years. Or a note that was in the famous collection of so and so. Building a pedigree allows the legacy of collectors from the past, present and future to be preserved.

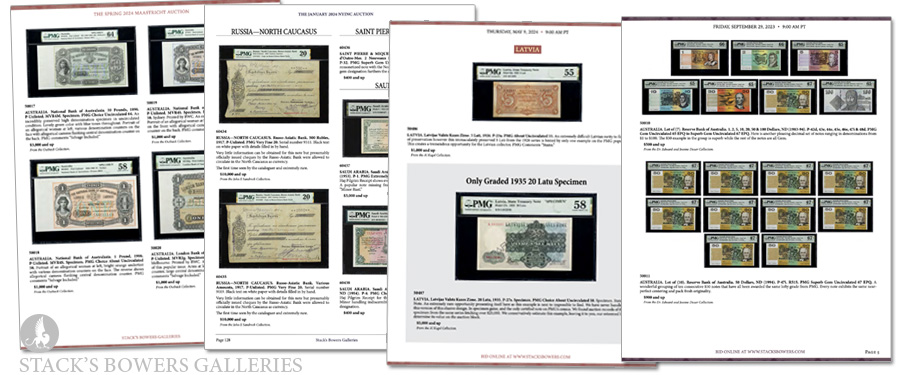

Even though pedigree research for paper money is in its infancy it should not be overlooked. While there are many limitations, catalogs in the 1970s started including more detail, including serial numbers, images and sometimes even the source of an item. This allows a dedicated collector to start building a pedigree to the present time. While the 1970s may seem recent, that’s still four or five decades ago. Over time many pedigrees have been lost, but others are waiting to be discovered, hidden in catalogs and price lists of years past.

What note in your collection has the oldest or most noteworthy pedigree? Let the author know at Dennis@stacksbowers.com and maybe we will feature it in an upcoming blog.