The End of Caesar on the Ides of March

Gaius Julius Caesar, commonly known by his nomen and cognomen (the second and third parts of his name based upon Latin naming conventions) came to prominence as both a general and a politician in the middle third of the first century B.C., forming a triumvirate with Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) and leading many successful military campaigns in Gaul and Britannia. His great accomplishments in the latter area, such as victories in the Gallic Wars, allowed him to amass incredible popularity, among his troops and his loving populace, who heard of his exploits in far away terrain. The Roman Senate, which increasingly viewed Caesar as a potential threat to the republic, ordered him to return to Rome—a return without his military might. Caesar, however, had different plans, choosing instead to enter what was Roman Italy proper by crossing her northern border, the Rubicon river, with a legion of his troops accompanying him. This act was considered by the Senate and other prominent Romans to be treasonous and an outright declaration of war upon the republic.

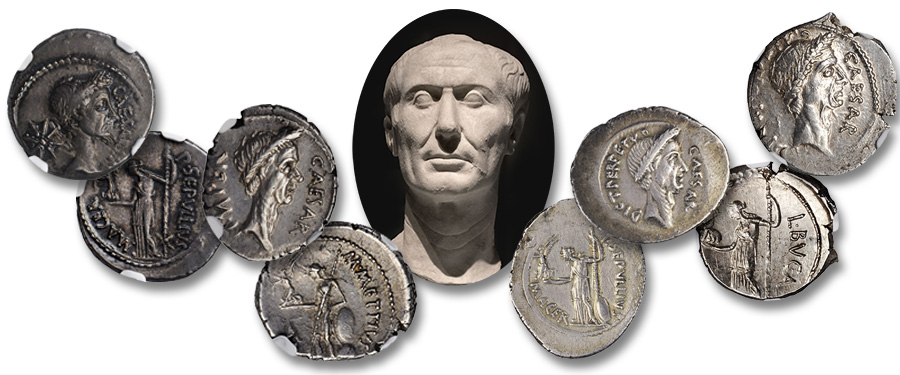

What would ensue was a four-year struggle, pitting Caesar’s populist and military factions against the senatorial and plebeian factions, with the former ultimately proving victorious. During this time, he was appointed to the position of dictator in order to better facilitate his agenda in the uncertainty of the civil war. Toward the end of the war, he was re-appointed, this time for a period of 10 years. This stranglehold on power allowed him virtual unchecked authority on all issues of the Roman state, giving him the ability to enact various reform measures, such as ordering a census, restructuring debt, and, rather importantly, reorganizing the calendrical system—ushering in the Julian calendar, a system that would serve much of Europe until the adoption of the Gregorian calendar over 1600 years later. However, this period also saw him achieve other goals that were seen by the remaining senators and plebeians as quite troubling to the rule of law, such as placing himself above checks and balances, having honorific and self-serving titles given to him, and even striking coins with his own likeness—a stark break in the tradition of placing personifications and deities from the Roman pantheon onto coinage. In February 44 B.C., Caesar was proclaimed dictator perpetuo (dictator for life)—a bridge too far for a group of conspirators wishing to restore the ideals of the seemingly long lost republic.

On the 15th of March—commonly referred to as the ‘ides’ of March, as Roman calendars had an unusual manner of reckoning the days of the month—Caesar was due to appear before the Senate. Unknown to him was the fact that numerous senators had been conspiring against him, seeking for an end to what they saw as his tyranny. While receiving appeals from one senator, he was confronted and slashed by a dagger. Confused and enraged, he pushed back, only to have the rest of the group descend upon him and produce their own daggers, each taking a stab at the man whom they once called their pater patriae (father of the country). Unable to see from the blood in his eyes, he tripped and fell, inviting even more stab wounds from the throng of assassins. In the end, his body was reported to have been stabbed 23 times, though only one was recounted by Suetonius as being the lethal blow. In the aftermath of this conspiracy there was confusion and anger among the populace, as many saw Caesar as a noble benefactor, and one who had cared for the commoners throughout the land. His assassins were looked upon very unfavorably, much to their surprise. What would follow would be a near decade-and-a-half power struggle with the aim to restore authority to Rome. This would present itself in the form of Caesar’s named heir and grand-nephew, Gaius Octavius, who took the name of Augustus as Rome’s first emperor. Any chance of restoring the republic— if Caesar even had such an inclination—died with him on the steps of the portico of the Theater of Pompey that fateful day in 44 B.C.

In our upcoming Official Auction of the N.Y.I.N.C. occurring next month in January 2020, we will be offering not just one extremely interesting and highly historic portrait denarius of Caesar, but four of these issues, each of which presents a very realistic rendition of the slain dictator, with his characteristic long neck and somewhat aged features. The condition of these spectacular pieces is extraordinary. All were struck during the time from 4-6 weeks before his assassination to just a few weeks after. The reverses each present an image of Venus, the goddess from whom Caesar claimed to be descended, adding even more appeal—albeit if only mythical—to these denarii. They offer an incredible opportunity to experience what the conspirators feared as they saw coins just like these in everyday transactions—"what can we do about this tyrant?"

To view our upcoming auction schedule and future offerings, please visit stacksbowers.com where you may register and participate in this and other forthcoming sales.

We are always seeking coins, medals, and pieces of paper money for our future sales, and are currently accepting submissions for our next Collectors Choice Online (CCO) auction will be in February 2020. Following that, our next showcase auction will be our Official Auction of the Hong Kong Show in March 2020—a monumental event that will mark our tenth anniversary of auctions in Asia! If you would like to learn more about consigning, whether a singular item or an entire collection, please contact one of our consignment directors today and we will assist you in achieving the best possible return on your material.