Excitement and more excitement! The catalog for our forthcoming sale of the Joel R. Anderson Collection of large-size paper money types is in the hands of our clients and is on the Internet. Part 1 will cross the block at the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Expo in Baltimore in just two weeks.

The Anderson Collection by definition includes notes from affordable and available to great rarities—among the last being unique and, often, the finest known.

This week’s showcase note is a trophy deluxe!

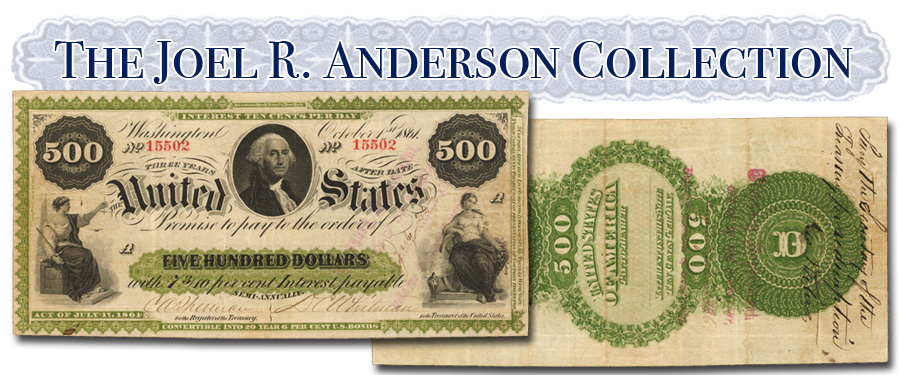

Important $500 Interest Bearing Note

Unique in Private Hands

The Friedberg Plate Note

Fr. 209a (W-3950). 1861 $500 Interest Bearing Note. PCGS Currency Very Fine 25. There are only two examples of this 1861 $500 Interest Bearing Note extant. The serial number 1 piece resides in the Bureau of Public Debt in Washington, DC, leaving this serial number 15502 note as the only collectible example of this early federal type. It is also the only one without cancellations, a notable difference making this one all the more special. These notes bore interest at a rate of 10 cents per day. There are light purple Treasury Department stamps on both the face and back of the note and a penned manuscript on the back reading "Pay the Secretary of the Treasury for redemption. Geo. Waters." A small concentration of pinholes is found at the left end of the note, otherwise the paper retains excellent body and is naturally bright. All of the printed inks are bold and illustrate the type in dramatic detail. It has been 13 years since collectors have had an chance to acquire this note. At that time it realized $299,000. Collectors interested in securing this prohibitively rare design type for their collections must seize the opportunity as it will not likely present itself again for quite some time.

PCGS Population 1; none finer. Unique in private hands and the only uncancelled note of the two.

From Kagin’s October 1995 Coin World ad; William Youngerman’s December 1996 Coin World ad; Heritage Auctions’ sale of February 2005, lot 16758.

Background to the Interest-Bearing Notes

In early 1861 the United States Treasury was running low on funds. With seven Southern states seceding and with the Union in threat of dissolution, the matter required resolution. There was uncertainty nationwide, as revealed in this letter from a banker, E. Clark, dated January 9, 1861. In Chicago for a visit, he wrote to an acquaintance, S.J. Kirkwood, in Des Moines City, Iowa:

"I arrived here this day and find the money market in a bad or feverish condition. I have met some Indiana bankers who say to me confidentially though they must suspend unless they get relief by N. York resuming specie payment. Their money is returning on them rapidly notwithstanding the demand for money [to be paid out].

"I find our branch has run down in coin $310,000 in ten days. Gold advances here 2% today. You may judge yourself what will be our condition in case this state of things continues. Ohio [banks] must suspend as they cannot weather the storm. This is the opinion of the best bankers here."

The Panic of 1861, little remembered today, caused 5,935 companies in the North to fail, at a loss of $178,632,170, and 1,058 in the South for $8,577,830. Money was in short supply. The Act of February 8, 1861, provided for a new issue of bonds denominated at $1,000 upward to be sold to augment the Treasury coffers. This was followed by the Act of March 2, 1861, which inaugurated what paper money collectors consider federal currency in a new era or setting. These are the first notes (or bonds) generally listed in popular numismatic references. An issue of 60-day notes was authorized, bearing interest equal to 6% annualized, to the amount of $10,000,000, with each bond having a face value of $1,000 or more. An additional larger amount (of which $25,364,450 was subsequently sold) had a two-year maturity. Advertisements were to be placed to entice brokers, banks, and exchange houses to bid for them, at a minimum of face value, after which the buyers would resell them to investors.

If buyers could not be found at par, the Treasury was authorized to produce a large quantity of smaller denomination bonds—we call them notes today—of $50 and higher, to be sold to the public. On the face of each note a space for the interest rate was left blank, to be filled in by pen. Other notes bore printing stating 6% annual interest for a two-year term. These were sold at a discount to securities houses and banks to reflect the interest at maturity. The buyers then retailed them to individual customers. Payment and receipt of Interest Bearing Notes was done in the office of L.E. Chittenden, Register of the Treasury.

The notes were printed under contract by the National Bank Note Company in New York City and did not bear the Treasury seal. Soon afterward the Civil War commenced. More demands were placed on Treasury funds, and reserves were further depleted. Financial help was desperately needed. The acts of July 17 and August 5, 1861, which also created Demand Notes, provided for additional Interest-Bearing Treasury Notes. As these notes were redeemable at face value in gold and silver coins and as they paid interest, the vast majority were cashed in. Today in 2018 the offering of any Interest-Bearing Note attracts wide attention, and the offering of a landmark rarity such as the Anderson note, unique in private hands, is spectacular.